MASSARO HOUSE

Massaro House is a private island residence inspired by designs of a never-constructed project conceived by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. It is located on the privately owned Petre Island (sometimes spelled Petra Island) in Lake Mahopac, New York, roughly 50 miles north of New York city. As designed it was known as the "Chahroudi House" for the client who commissioned it; as built it gained the name of its owner, Joseph Massaro.

WILLITS HOUSE

The Ward W. Willits House is a building designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Designed in 1901, the Willits house is considered the first of the great Prairie houses. Built in the Chicago suburb of Highland Park, Illinois, the house presents a symmetrical facade to the street. One of the more interesting points about the house is Wright's ability to seamlessly combine architecture with nature.

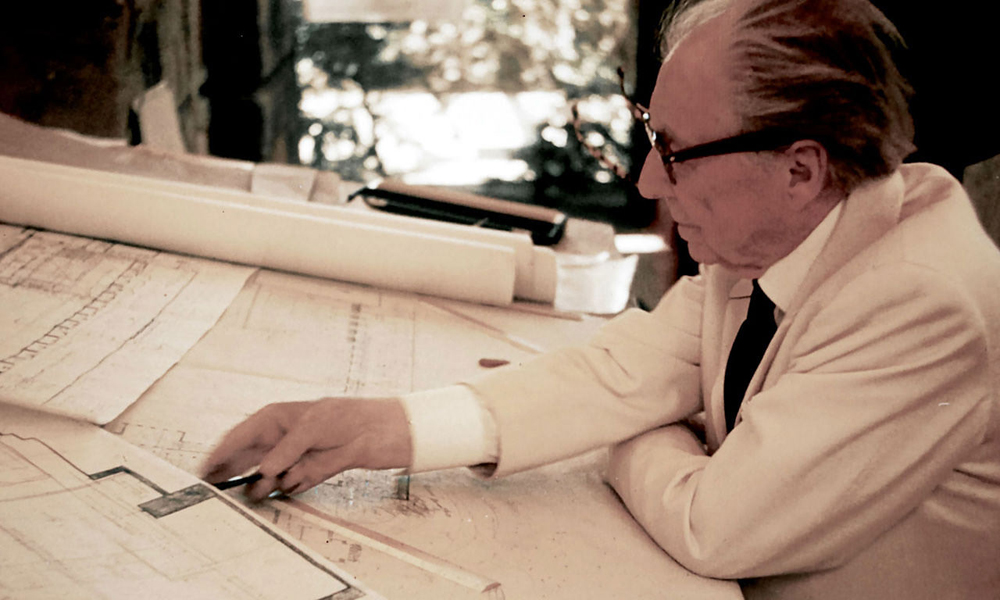

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

Frank Lloyd Wright (born Frank Lincoln Wright, June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, interior designer, writer and educator, who designed more than 1,000 structures, 532 of which were completed. Wright believed in designing structures that were in harmony with humanity and its environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was best exemplified by Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture". His creative period spanned more than 70 years. Wright was the pioneer of what came to be called the Prairie School movement of architecture and he also developed the concept of the Usonian home in Broadacre City, his unique vision for urban planning in the United States. In addition to his houses, Wright designed original and innovative offices, churches, schools, skyscrapers, hotels, museums and other structures. He often designed interior elements for these buildings as well, including furniture and stained glass. Wright wrote 20 books and many articles and was a popular lecturer in the United States and in Europe. Wright was recognized in 1991 by the American Institute of Architects as "the greatest American architect of all time". His colorful personal life often made headlines, notably for leaving his first wife, Catherine Lee "Kitty" Tobin for Mamah Borthwick Cheney, the murders at his Taliesin estate in 1914, his tempestuous marriage and divorce with second wife Miriam Noel, and his relationship with Olga (Olgivanna) Lazovich Hinzenburg, whom he would marry in 1928.

CONTENT MANAGEMENT (CMS)

In the "Falling Water" text below you will find a second option for content management. (allowing for text editing, photo, Vimeo, Youtube, etc. insertion) This option allows for the online editing on the webpage, no separate backend editor…what you see is what you get. If you would like to try this demo, press the hotkey Shift + Control + x; The demo password is, demo, Enter the password and press enter/return. Demo mode edits are non-destructive, server saving is disabled.

FALLING WATER

In 1909, after 20 years of marriage, Wright suddenly abandoned his wife, children and practice and moved to Germany with a woman named Mamah Borthwick Cheney, the wife of a client.

Working with the acclaimed publisher Ernst Wasmuth, while in Germany Wright put together two portfolios of his work that further raised his international profile as one of the leading living architects. In 1913, Wright and Cheney returned to the United States, and Wright designed them a home on the land of his maternal ancestors in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Named Taliesin, Welsh for "shining brow," it was one of the most acclaimed works of his life. However, tragedy struck in 1914 when a deranged servant set fire to the house, burning it to the ground and killing Cheney and six others. Although Wright was devastated by the loss of his lover and home, he immediately began rebuilding Taliesin in order to, in his own words, "wipe the scar from the hill."

The next year, in 1915, the Japanese Emperor commissioned Wright to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. He spent the next seven years on the project, a beautiful and revolutionary building that Wright claimed was "earthquake proof." Only one year after its completion, the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 devastated the city and tested the architect's claim. Wright's Imperial Hotel was the city's only large structure to survive the earthquake intact. Returning to the United States, he married a sculptor named Miriam Noel in 1923; they stayed together for four years before divorcing in 1927. In 1925 another fire, this one caused by an electrical problem, destroyed Taliesin, forcing him to rebuild it once again. In 1928, Wright married his third wife, Olga (Olgivanna) Ivanovna Lazovich—who also went by the name Olga Lazovich Milanov, after her famous grandfather Marko.

ROBIE HOUSE (UNIVERISY OF CHICAGO)

The Frederick C. Robie House is a U.S. National Historic Landmark on the campus of the University of Chicago in the South Side neighborhood of Hyde Park in Chicago, Illinois, at 5757 S. Woodlawn Avenue. Built between 1909 and 1910, the building was designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright and is renowned as the greatest example of the Prairie School style, the first architectural style considered uniquely American. It was designated a National Historic Landmark on November 27, 1963 and was on the very first National Register of Historic Places list of October 15, 1966.

The Robie House is one of the best known examples of Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie style of architecture. The term was coined by architectural critics and historians (not by Wright) who noticed how the buildings and their various components owed their design influence to the landscape and plant life of the midwest prairie of the United States. Typical of Wright's Prairie houses, he designed not only the house, but all of the interiors, the windows, lighting, rugs, furniture and textiles. As Wright wrote in 1910, "it is quite impossible to consider the building one thing and its furnishings another. ... They are all mere structural details of its character and completeness."

The Robie House was one of the last houses Wright designed in his Oak Park, Illinois home and studio and also one of the last of his Prairie School houses. According to the Historical American Buildings Survey, the city of Chicago's Commission on Chicago Architectural Landmarks stated: "The bold interplay of horizontal planes about the chimney mass, and the structurally expressive piers and windows, established a new form of domestic design." Because the house's components are so well designed and coordinated, it is considered to be a quintessential example of Wright's Prairie School architecture and the "measuring stick" against which all other Prairie School buildings are compared.

The house and the Robie name were immortalized in Ernst Wasmuth's famous 1910 publication Ausgefuhrte Bauten und Entwurfe von Frank Lloyd Wright (Completed Buildings and Projects of Frank Lloyd Wright, a.k.a. "The Wasmuth Portfolio"). This publication featured most of Wright's designs, including those unbuilt, during his Oak Park years and brought them to the attention of students of the Bauhaus school in Germany and the De Stijl school in the Netherlands. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe among other great 20th Century architects, claimed Wright was a major influence on their careers. Mies van der Rohe later visited the Robie House and Wright's home (Taliesin) in Spring Green, WI.